Remote Method Invocation (RMI) and Remote Procedure Call (RPC) are two important concepts in Java that allow for distributed computing. Both RMI and RPC enable software components to communicate with each other over a network, allowing code to be executed on different machines without the need for manual intervention. In this blog post, we will discuss what RMI and RPC are, how they differ from one another, their advantages/disadvantages as well as an example of each in Java.

What is RMI

At its core, Remote Method Invocation is a way of calling methods on remote objects over a network connection using the Object Request Broker Architecture (ORB). It provides developers with the ability to execute code remotely without having any knowledge about where or how it is being run – all you need is an interface definition file (.idl file), which describes your object’s methods signatures and return types along with some additional information related to security etc., then you can use it just like any other local object! The main benefit here lies in its flexibility; since there’s no requirement for manual coding or compilation when making changes across multiple systems simultaneously - instead all that needs doing is updating one centralised IDL file.

Remote invocation is nothing new. For many years C programmers have used remote procedure calls (RPC) to execute a C function on a remote host and return the results. The primary difference between RPC and RMI is that RPC, being an offshoot of the C language, is primarily concerned with data structures. It’s relatively easy to pack up data and ship it around, but for Java, that’s not enough. In Java we don’t just work with data structures; we work with objects, which contain both data and methods for operating on the data. Not only do we have to be able to ship the state of an object (the data) over the wire, but also the recipient has to be able to interact with the object (use its methods) after receiving it.

Now let us first understand some concepts regarding RMI and how it works. At first lets understad what are Remote and Non Remote Objects

Remote and Non Remote Obj

Before an object can be used with RMI, it must be serializable. But that’s not sufficient. Remote objects in RMI are real distributed objects. As the name suggests, a remote object can be an object on a different machine; it can also be an object on the local host. The term remote means that the object is used through a special kind of object reference that can be passed over the network. Like normal Java objects, remote objects are passed by reference. Regardless of where the reference is used, the method invocation occurs at the original object, which still lives on its original host. If a remote host returns a reference to one of its objects to you. Then you call that object’s methods; the actual method invocations will happen on the remote host, where the object is.

Non remote objects are simpler. They are just normal serializable objects. (You can pass these over the network). The catch is that when you pass a non remote object over the network it is simply copied. So references to the object on one host are not the same as those on the remote host. Non remote objects are passed by copy (as opposed to by reference).

Stub

Stub is used in the implementation of remote objects. When you invoke a method on a remote object (which could be on a different host), you are actually calling some local code that serves as a proxy for that object. This is the stub. (It is called a stub because it is something like a truncated placeholder for the object.)

The stub object on the client machine builds an information block and sends this information to the server.

The block consists of

- An identifier of the remote object to be used

- Method name which is to be invoked

- Parameters to the remote JVM

Skeleton

The skeleton is another proxy that lives with the real object on its original host. It receives remote method invocations from the stub and passes them to the object.

The skeleton object passes the request from the stub object to the remote object. It performs the following tasks

- It calls the desired method on the real object present on the server.

- It forwards the parameters received from the stub object to the method.

Before creatin stubs and skeletons we need to create remote object and understand how it works

Remote Object

The first thing to do is to create an interface that will provide the description of the methods that can be invoked by remote clients. This interface should extend the Remote interface and the method prototype within the interface should throw the RemoteException.

Remote objects are objects that implement a special remote interface that specifies which of the object’s methods can be invoked remotely. The remote interface must extend the java.rmi.Remote interface. Your remote object will implement its remote interface; as will the stub object that is automatically generated for it. In the rest of your code, you should then refer to the remote object as an instance of the remote interface—not as an instance of its actual class. Because both the real object and stub implement the remote interface, they are equivalent as far as we are concerned (for method invocation); locally, we never have to worry about whether we have a reference to a stub or to an actual object. This “type equivalence” means that we can use normal language features, like casting with remote objects. Of course public fields (variables) of the remote object are not accessible through an interface, so you must make accessor methods if you want to manipulate the remote object’s fields.

All methods in the remote interface must declare that they can throw the exception java.rmi.RemoteException . This exception (actually, one of many subclasses to RemoteException) is thrown when any kind of networking error happens: for example, the server could crash, the network could fail, or you could be requesting an object that for some reason isn’t available.

Here’s a simple example of the remote interface that defines the behavior of RemoteObject; we’ll give it a method that can be invoked remotely

| |

when we implement this object its called remote object which is for the server. For the client, the RMI library will dynamically create an implementation Stub.

implementation

| |

It’d be unusual for our remote object to throw a RemoteException since this exception is typically reserved for the RMI library to raise communication errors to the client. Leaving it out also has the benefit of keeping our implementation RMI-agnostic. Also, any additional methods defined in the remote object, but not in the interface, remain invisible for the client.

Once we create the remote implementation, we need to bind the remote object to an RMI registry.

RMI Registry

The registry is the RMI phone book. You use the registry to look up a reference to a registered remote object on another host. We’ve already described how remote references can be passed back and forth by remote method calls. But the registry is needed to bootstrap the process: the client needs some way of looking up some initial object.

The registry is implemented by a class called Naming and an application called rmiregistry . This application must be running on the local host before you start a Java program that uses the registry. You can then create instances of remote objects and bind them to particular names in the registry. (Remote objects that bind themselves to the registry sometimes provide a main( ) method for this purpose.) A registry name can be anything you choose; it takes the form of a slash-separated path. When a client object wants to find your object, it constructs a special URL with the rmi: protocol, the hostname, and the object name. On the client, the RMI Naming class then talks to the registry and returns the remote object reference.

So before registering in RMI registry we need to create a stub

| |

We use the static UnicastRemoteObject.exportObject method to create our stub implementation. The stub communicates with the server over the underlying RMI protocol.

The first argument to exportObject is the remote server object. The second argument is the port that exportObject uses for exporting the remote object to the registry.

Giving a value of zero indicates that we don’t care which port exportObject uses, which is typical and so chosen dynamically.

UnicastRemoteObject

The actual implementation of a remote object (not the interface we discussed previously) will usually extend java.rmi.server.UnicastRemoteObject. This is the RMI equivalent to the familiar Object class. When a subclass of UnicastRemoteObject is constructed, the RMI runtime system automatically “exports” it to start listening for network connections from remote interfaces (stubs) for the object. Like java.lang.Object, this superclass also provides implementations of equals( ) , hashcode( ), and toString( ) that make sense for a remote object.

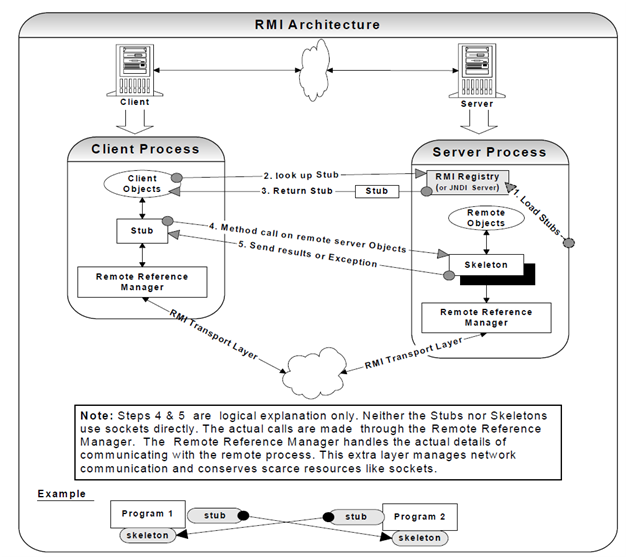

RMI Architecture

Now lets create a RMI registry

Creating RMI Registry

We can start up a registry local to our server or as a separate stand-alone service. Here we will create for local

| |

This creates a registry to which stubs can be bound by servers and discovered by clients. Also, we’ve used the createRegistry method, since we are creating the registry local to the server.

By default, an RMI registry runs on port 1099. Rather, a different port can also be specified in the createRegistry factory method.

But in the stand-alone case, we’d call getRegistry, passing the hostname and port number as parameters.

Now we have to bind the stub which is generated by rmic to registry

Bind Stub

An RMI registry is a naming facility like JNDI etc. We can follow a similar pattern here, binding our stub to a unique key: here its MessageService

| |

after registering the stub in RMI registry we need to create a client.

Create Client

To do this, we’ll first locate the RMI registry. In addition, we’ll look up the remote object stub using the bounded unique key.

And finally, we’ll invoke the send method:

| |

Because we’re running the RMI registry on the local machine and default port 1099, we don’t pass any parameters to getRegistry. Indeed, if the registry is rather on a different host or different port, we can supply these parameters. Once we lookup the stub object using the registry, we can invoke the methods on the remote server.