To generate random numbers in java there are 4 given ways by the api. In java 17 new generic api and some other api’s was introduced.

- Random Class

- ThreadLocalRandom Class

- SecureRandom Class

- SplitabbleRandom Class

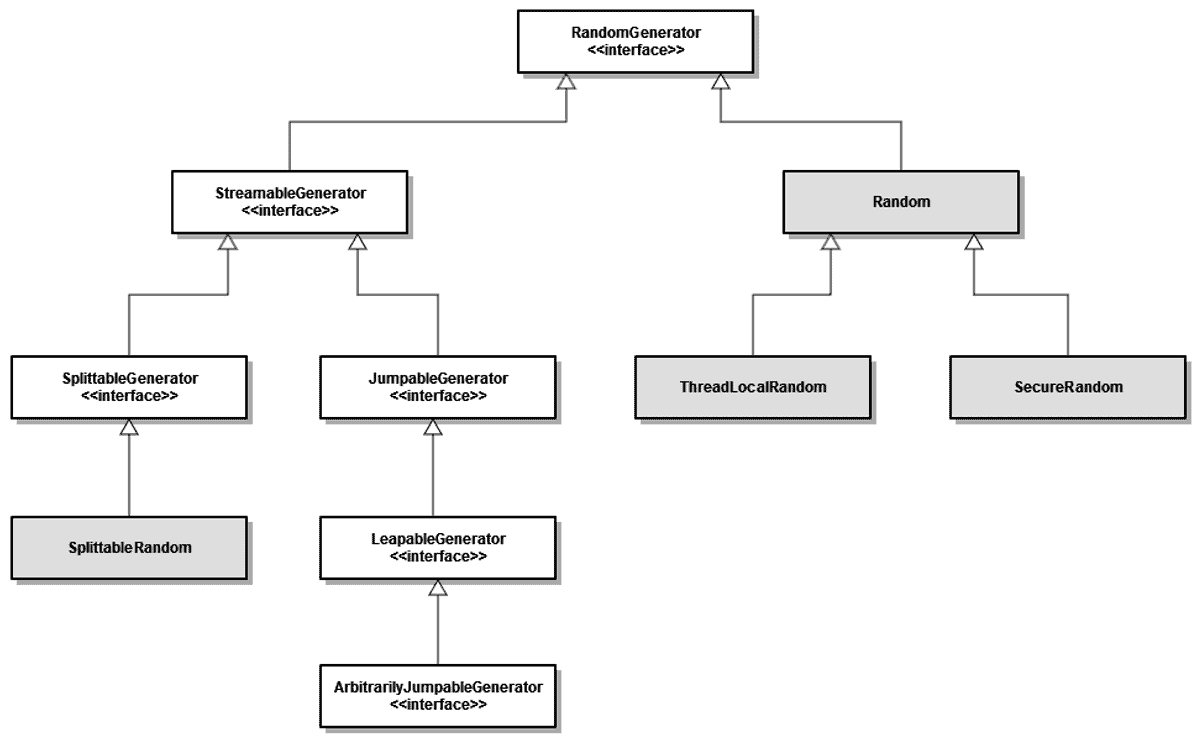

Fig: Java 17 new RandomGenerator Interface.

Fig: Java 17 new RandomGenerator Interface.

Random:

The Random Class of the java.util package is used for generating a stream of pseudorandom numbers. It uses a 48-bit seed, and using a Linear Congruential Formula.

If we create two instances of the Random class with the same seed value and call the same sequence of methods for each . They both will return identical sequences of numbers. This property is enforced by specific algorithms defined for this class. The algorithms use a protected utility method which upon invocation can give up to 32 pseudorandomly generated bits.

Instances of Random are thread–safe. Although, if the same instances are used across threads they may suffer from contention and result in poor performance. The Instances of Random are not cryptographically safe. So should not be used for security-sensitive applications.

| |

ThreadLocalRandom:

ThreadLocalRandom is a combination of the ThreadLocal and Random classes. Its isolated to the current thread. So it achieves better performance in a multi-threaded environment. It avoids any concurrent access to instances of Random.

The random number obtained by one thread is not affected by the other thread. Whereas java.util.Random provides random numbers globally.

Also, unlike Random, ThreadLocalRandom doesn’t support setting the seed explicitly. Instead, it overrides the setSeed(long seed) method. Its inherited from Random and always throw an UnsupportedOperationException if called.

So now we will take a detour and try to understand what is Thread contention which is the reason behind Random classes result in poor performance while being in multi-threaded env

Thread Contention:

when two threads try to access either the same resource or related resources. At least one of the contending threads runs slower than it would if the other thread(s) were not running. This situation is called thread contention.

The most obvious example of contention is on a lock. If thread A has a lock and thread B wants to acquire that same lock, thread B will have to wait until thread A releases the lock.

For example, consider a thread that acquires a lock, modifies an object, then releases the lock and does some other things. If two threads are doing this, even if they never fight for the lock, the threads may run much slower than they would if only one thread was running.

Why? Say each thread is running on its own core on a modern x86 CPU and the cores don’t share an L2 cache. With just one thread, the object may remain in the L2 cache most of the time. With both threads running, each time one thread modifies the object, the other thread will find the data is not in its L2 cache because the other CPU invalidated the cache line.

So far, we can see that the Random class performs poor in highly concurrent environments. To better understand this, let’s see how one of its primary operations, next(int), is implemented

| |

This portion of code is copied from openJDK and here we can see it implements Linear Congruential Generator algo to generate pseudo random numbers.It’s obvious that all threads are sharing the same seed instance variable.

To generate the next random set of bits, it first tries to change the shared seed value atomically via compareAndSet or CAS for short.

When multiple threads attempt to update the seed concurrently using CAS, one thread wins and updates the seed, and the rest lose. Losing threads will try the same process over and over again until they get a chance to update the value and ultimately generate the random number.

This algorithm is lock-free , and different threads can progress concurrently. However, when the contention is high, the number of CAS failures and retries will hurt the overall performance significantly.

On the other hand, the ThreadLocalRandom completely removes this contention, as each thread has its own instance of Random and, consequently, its own confined seed.

current() in ThreadLocalRandom

This method returns ThreadLocalRandom instance for the current thread. ThreadLocalRandom can be initialized as below.

| |

nextInt(int least,int bound) returns the next pseudo number . We can pass the least limit and max limit. There are more method like nextDouble, nextLong. So finally we can get random number as below

| |

now writing a simple implementation of ThreadLocalRandom.

| |

In the example there is a ForkJoinTask implementation. Also inside exec() method of ForkJoinTask, we obtained the random number by ThreadLocalRandom. We have run two ForkJoinTask to test the random number generation. Run the example many time and every time you will get random numbers. Sample output is as below.

SecureRandom

Standard JDK implementations of java.util.Random use a Linear Congruential Generator (LCG) algorithm for providing random numbers. The problem with this algorithm is that it’s not cryptographically strong. In other words, the generated values are much more predictable, therefore attackers could use it to compromise our system.

The java.security.SecureRandom class does not actually implement a pseudorandom number generator (PRNG) itself. It uses PRNG implementations in other classes to generate random numbers. So the randomness of the random numbers and security and performance of SecureRandom depends on the algorithm chosen. If you want cryptographically strong randomness, then you need a strong entropy source. Entropy here refers to the randomness collected by an operating system or application. The entropy source is one which collects random data and supplies to destination.

The file which controls the configuration of the SecureRandom API is located at: $JAVA_HOME/lib/security/java.security

We can select the source of seed data for SecureRandom by using the entropy gathering device specified in securerandom.source property in java.security file.

E.g.

securerandom.source=file:/dev/random

Way of initializing a SecureRandom and get a cryptographycally strong secure random numbers.

| |

another way of creating instance will be

| |

this getInstanceStrong() is a blocking call.

Difference between them : the first instance uses /dev/urandom. The second instance uses /dev/random. /dev/random blocks the thread if there isn’t enough randomness available. Whereas /dev/urandom will never block.

Believe it or not, there is no advantage in using /dev/random over /dev/urandom. They use the same pool of randomness under the hood. They are equally secure. If you want to safely generate random numbers, you should use /dev/urandom.

The only time you would want to call /dev/random is when the machine is first booting and entropy has not yet accumulated. Most systems will save off entropy before shutting down. so that some is available when booting. so this is not an issue if you run directly on hardware.

But, it might be an issue if you don’t run directly on hardware. If you are using a container based solution like Docker or CoreOS. You might start off from an initial image, and so may not be able to save state between reboots. And in a multi-tenant container solution, there is only one shared /dev/random which may block.But the work around in these cases is to seed /dev/random with a userspace solution, either using an entropy server for pollinate, or a CPU time stamp counter for haveged. Either way, by the time the JVM starts, the system’s entropy pool should already be up to the job.

| |

SplittableRandom

SplittableRandom is a really interesting class, that was added in the scope of Java 8.

The differences with a Random class are:

It passes a Diehard test, that means it can generate more quality pseudorandom numbers. it’s not thread-safe, but faster than Random and method split creates a new SplittableRandom instance that shares no mutable state with the current instance. It’s useful for parallel streams.

it doesn’t extend a Random class like SecureRandom and ThreadLocalRandom.

Let’s take a look at code examples.

The most common task is to generate a random number in the range:

| |

Generate an array of random ints in the range:

| |

As you see this class has stream-friendly API. Since Java 10 was added SplittableRandom.nextBytes, so you can use it as well. Java 17 added RandomGenerator interface and SplittableRandom now extends that as we can see from the Figure.

Will post another blog post for SplittableRandom and how its used in monte carlo simulation